Squeezing the Apple for All Its Juice

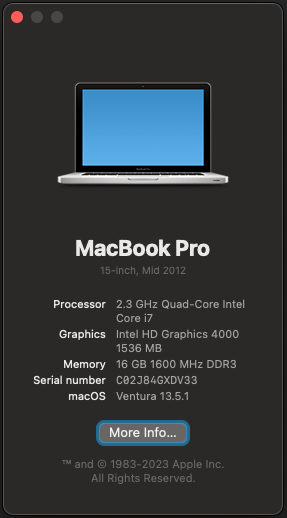

It’s 2025, and I run a Mid 2012 MacBook as my daily driver with macOS Ventura installed on it.

Why? With recent Apple products priced out of my range, I can’t justify a new or even official Apple Refurbished laptop right now as I look for an engineering role, and especially not when I can use my engineering brain to find a solution.

At this point in my life, my brain is Mac-mapped. Besides my 2012 MacBook Pro, I also have a 2013 iMac (running macOS Sonoma). A few years ago I was looking to update my iMac so that the security updates would be current and I would be able to run the most recent versions of applications. Apple said, “Nah, buy a new computer, cheapskate.” “Um, excuse me? OK then, challenge accepted.” I thought, what can I do with what I got? There’s no way I’m just going to go along with Apple’s planned obsolescence.

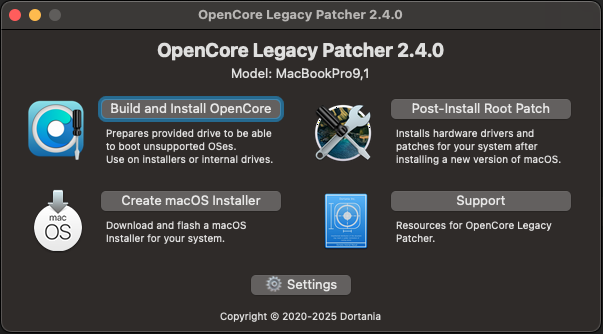

In comes OpenCore, the boot loader, and its GUI companion, OpenCore Legacy Patcher, to modify macOS on the fly to work with older hardware.

High Level Overview

According to the README, OpenCore Legacy Patcher (OCLP) is:

A Python-based project revolving around Acidanthera’s OpenCorePkg and Lilu for both running and unlocking features in macOS on supported and unsupported Macs.

Our project’s main goal is to breathe new life into Macs no longer supported by Apple, allowing for the installation and usage of macOS Big Sur and newer on machines as old as 2007.

OpenCorePkg (OpenCore) is the boot loader behind the GUI interface of OCLP. It was the successor to Clover, which had been a favorite of Hackintosh users for running macOS on unsupported hardware. The key feature of OpenCore is kext injection.

Kexts are “kernel extensions”, snippets of code that modify the macOS kernel to enable compatibility with system components. When OpenCore boots the macOS kernel, it modifies the OS on the fly during each boot so that you don’t have to worry about directly modifying the OS.

Modifying macOS directly was the first way to run macOS on unsupported hardware. Scripts were created and shared to do this, but maintaining your machine became tricky when system updates were executed. With each update you would have to re-run the scripts, and that assumes the update didn’t accidentally render your machine unbootable.

Greg Gant, in his write up for OCLP, includes a great summary of how macOS became more closed at the system level over time to reduce possible malware vectors at the OS level. This closing at the system level removed permissions for the root user to edit the OS, thus scripts like DOSDude1’s wouldn’t work anymore.

So kext injection became the way to go, but managing the configuration of OpenCore was still a little advanced, which limited its use to power users. Much like the OS modifying scripts, config files were shared for certain sets of hardware, you could edit them to your specific set of hardware as needed.

OCLP was born out of the goal to increase access and use of OpenCore for users that aren’t super knowledgeable about OS patching (me). OCLP provides a GUI interface along with maintained collections of patches for hardware. To use OpenCore, now a user only needs to know the model of their mac and the target OS they want to install.

My Experience with OCLP

OCLP has been my lifeline in the last year. I actually bought my 2012 MacBook Pro in 2024 (shout out to Unicom in Cranston, RI) when I was going through the Operation Spark bootcamp. Running this machine as my daily driver has broadened my perspective on how long hardware can be useful as well as what my actual needs and limitations are as a developer.

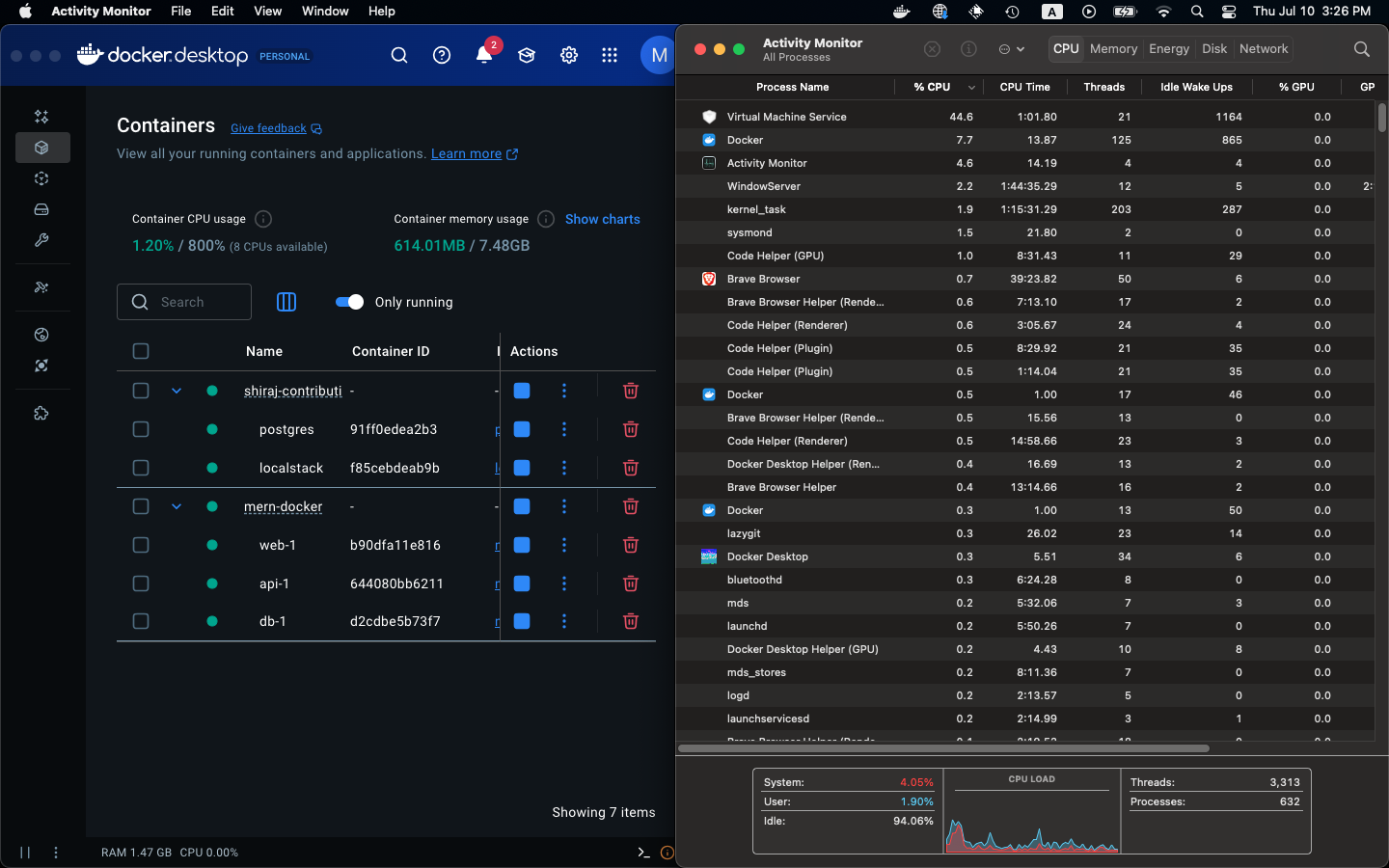

My machine meets my needs pretty much completely. A few limitations I’ve run into: running multiple Docker containers at a time and running Zoom and Chrome at the same time. It boils down to memory usage and graphics processing. With Sequoia on my iMac, the dynamic wallpapers don’t work, which is purely cosmetic.

These limitations are inconveniences I can live with. I can still run more than one Docker container concurrently, but I have to limit what else is running on my computer at the same time and monitor the ventilation / how hot it’s getting. Zoom, as expected, uses a big portion of memory and CPU, I use it as least as possible. Chrome was also using a lot of memory, then someone mentioned Brave uses less, so I switched to Brave and that has worked better for me, with the bonus of a default adblocker.

Currently, I’m staying with Ventura on my laptop because there are graphics driver bugs that might be critical on my MacBook Pro. I’ll experiment later, but right now I’m staying with what definitely works.

Reflections

I’m proud that I can develop all I need on a machine that nobody expects to be running. I’m also keeping completely viable hardware out of the landfill as long as possible. Reduce and Reuse, two of the Three R’s in action!

I went this route for practicality and frugality. For me, a welcomed challenge. I kinda like friction in my life because it usually means I’ll learn something and be better prepared for other challenges. If I can fix something myself, that’s the road I’m going to take. It’s all additive knowledge and it makes life more interesting.

I 100% recommend OCLP to anyone who wants to run their older Macs. Maybe you just want an onboard CD drive again, maybe you want to save viable components from the landfill, or maybe it’s your best option for a working Mac without shelling out at least a grand. I’ve installed OS Ventura on my 2012 MacBook Pro and my friend’s 2011 27" iMac (to run the latest Adobe Creative apps), and OS Sequoia on my 2013 iMac. No major hiccups yet!

Which brings me to my call to action:

Throw Apple’s short support window out the window and squeeze your Apple for all its juice!

Recommended resources:

- Official docs and step by step instructions.

- Video: Install macOS Sonoma on Unsupported Macs using OpenCore (Step-by-Step Tutorial)

- Video: OpenCore & OCLP Explained (OpenCore Legacy Patcher)